Working the system: 3 ways planners can defy the odds to promote good health for all of us

Jennifer Kent,University of Sydney

Many of the chronic and costly diseases Australians face are related to how we live in cities. The speed of modern life clashes with poorly designed urban areas. As a result, health-promoting activities, such as regular physical activity, community interaction and the preparation of healthy food, become low priorities.

We know better urban planning can encourage healthier behaviours. Providing infrastructure for walking and cycling is a prime example. Yet there are other, often overlooked, ways that urban planners are on the front line when it comes to promoting the health of Australians. In particular, the way cities are planned can reduce inequities in both access to health services and health outcomes. This has important implications for the health of individuals and their communities.

Urban planners are well versed in the fundamentals of planning the equitable city. But planners must work within the constraints of our political systems and prevailing approaches to government. Our recent analysis of health and urban planning in Australia identified a few key ways urban planners can “work the system” to promote health equity.

Why is equity so important for health?

Promoting equity is important for health because there is a social gradient to the differences between people’s health. In general, the higher a person’s socio-economic position, the healthier he or she is. People from poorer social or economic circumstances have higher rates of illness and disability, and live shorter lives.

Differences in life expectancies across the nation illustrate this. In 2016, a man born in remote New South Wales had alife expectancy 13 years lessthan a man born in the affluent suburb of Mosman in Sydney.

To promote equity, we need to define what we are seeking to equalise. In this case, it is the distribution of the social determinants of health.

These determinants are the conditions in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age. Factors such as income, education, employment, empowerment and social support can strengthen or undermine health and well-being.

Our planners have access to the data and the grounded knowledge required to expose gaps in services. For example, a local infrastructure planner can readily identify the communities that lack internet broadband access but need it. A transport planner working for Sydney’s City Rail knows all too well which train service is unreliable, and which train station is routinely missed during the peak because of overcrowding.

Planners also have the skills and insights to raise concerns about shortages of residential housing stock, before these trigger the kind of housing affordability crises we have seen recently in Australian cities.

Planners need to ‘work the system’

The real challenge for planners promoting equity in Australia is the need to work within the constraints of the nation’s dominant political economy. In Australia today, we have a neoliberal system, epitomised by “the subjugation of the public to the private, the state to the market, the social to the economic”, as John Clarke put it. The result of this has been a progressive withdrawal of government involvement in many areas since the latter half of the 20th century.

Our recent analysis of health and urban planning in Australia provides several recommendations on how urban planners can work within this system to promote health equity.

Play to emotions

The first is to harness the power of human health’s emotive appeal. Relative to other planning concerns, such as environmental sustainability, health is an issue that appeals more directly to the individual.

By making clear the links between good planning principles and human health, planners can leverage this emotion to promote concepts that might otherwise be ignored in developer-driven agendas. The protection of green open spaces for physical activity and community connection is a good example. By pointing out how important these things are for human health, urban planners can make a compelling and robust case for preserving these spaces.

Speak the language of money

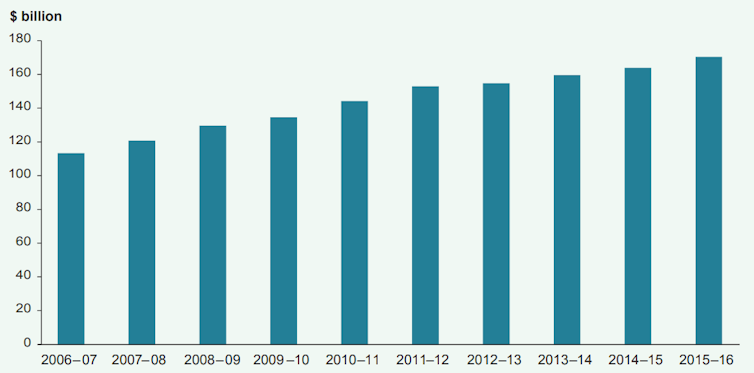

A second way that planning for health can leverage space in a neoliberal system is to speak the language of the market. In 2016-17, Australia spent A$180.7 billion on health. This spending increases from year to year, outpacing growth in inflation, population or the economy.

Most of this funding is dedicated to treating people once they are sick, rather than preventing illness. But prevention would produce large cost-savings. These savings can be captured in decision-making tools such as cost-benefit analysis.

Planners are in a powerful position to work with public health professionals to develop a deeper understanding of the health cost savings to be made from better urban planning decisions.

Enlist trusted figures

Finally, health can be promoted by harnessing the power of the health fraternity. Australian research shows the voice of a well-versed and respected individual can often make the difference when it comes to preserving a piece of open space, funding a cycleway or protecting the use of land for farmers’ markets.

Australians hold health professionals in high esteem. Polling company Roy Morgan conducts an Image of Professions Survey, asking Australians to rank 30 professions by characteristics such as ethics and honesty. Medical professionals, such as nurses, doctors, pharmacists and dentists, have consistently featured in the top five. These trusted professionals could be influential voices for healthy built environment agendas.

Our cities can and should be places that promote good health for everyone who lives in them. Quite simply, this means the (re)prioritisation of well-being over economic growth.

This is a crucial barrier to planning healthy built environments in Australia. Yet it is not insurmountable. Indeed, the key to overcoming it may well be harnessing the power of health as a significant concern for all.

The ideas in this article are taken from a new book, Planning Australia’s Healthy Built Environments. Join Jennifer Kent at the Festival of Urbanism in Sydney on September 9 to explore these issues.![]()

Jennifer Kent, Research Fellow, Urban and Regional Planning, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jobs Just For You, The Planning Professional

Our weekly or daily email bulletins are guaranteed to contain only fresh employment opportunities