Sydney’s largest public housing estate is being redeveloped, but not all these homes need to be demolished

Alistair Sisson, Macquarie University; Cameron Logan, University of Sydney; Michael Zanardo, Monash University, and Rebecca McLaughlan, University of Sydney

The New South Wales government is forging ahead with renewal of the state’s largest public housing estate. Developer Stockland and three community housing providers are contracted to deliver the first stage nearly a decade after it was announced. Some 749 homes are to be demolished and replaced with more than 3,000 new apartments.

Following the Minns government’s changes in 2023, Waterloo South will comprise 30% social housing, 20% affordable housing and 50% market-rate housing. Plans for the 1,200-plus homes in Waterloo Central and North are yet to be confirmed.

The contentious 15-year project is due to start in 2027. It has been pitched as replacing ageing homes that are no longer “fit for purpose”, while increasing housing supply.

The former Coalition government’s housing minister, Brad Hazzard, described the homes in Waterloo as “terrible”. Local Labor MP Ron Hoenig said they were “well past their renewal date”.

One might expect, then, that the estate housing is badly designed and dilapidated. However, no comprehensive condition assessment nor refurbishment feasibility study has been made public.

Our research examined the quality of the Waterloo housing, using the original architectural drawings and field-based observations. While this approach doesn’t account for maintenance issues, it shows the underlying quality of much of the estate is good by today’s standards. This finding complicates the rationale for redevelopment.

Diverse housing histories

When we think of a housing “estate”, we often think of a swathe of homogenous homes – uniform apartment blocks or “cookie cutter” suburban housing. The Waterloo estate, in contrast, has diverse housing types built over almost 40 years.

The first homes were four small, three-storey apartment blocks built in 1948 at the start of the post-war public housing boom. By the early 1960s, the NSW Housing Commission had added several more low-rise complexes occupying whole street blocks.

It scaled up its ambition later that decade with larger complexes of 50-plus units and up to six storeys.

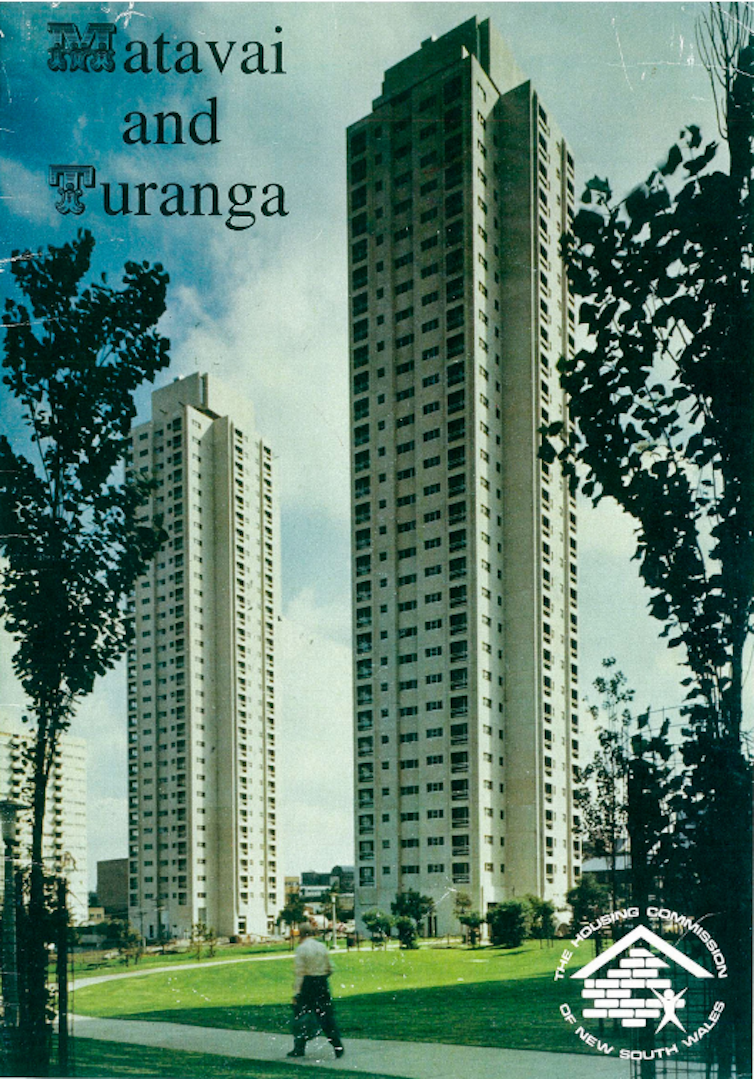

These buildings would soon be dwarfed in the 1970s by the Endeavour Project, including the famous (or infamous) four 17-storey slabs and two 30-storey towers. These buildings, more resonant with the popular image of public housing, make up Waterloo North and Central.

The backlash against this style of development inspired a broader shift within the NSW Housing Commission. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, it constructed complexes that were more modest in scale, yet architecturally striking. This includes the Drysdale and Dobell buildings designed by Tao Gofers and Penny Rosier – later siblings to the Sirius building.

So the estate comprises a diverse cross-section of 20th-century public housing. Is it all obsolete? This is the question we sought to answer.

Evaluating Waterloo

Since 2015, the Apartment Design Guide has set out the benchmarks for apartment housing in NSW. These guidelines reflect academic and industry research evidence on the environmental and spatial qualities that enhance physical and psychological wellbeing. These qualities include natural light, fresh air, visual privacy, accessibility, liveability, thermal comfort and access to nature and community.

We compared the architectural plans for Waterloo’s four main housing types – three-storey walk-ups, six-storey courtyard blocks, 17-storey slabs and 30-storey towers – with the controls outlined in the guide.

All four types compare well against the recommendations on access to light and air, thermal comfort and visual and acoustic privacy. All dwellings have large windows to provide excellent daylight and fresh air. Rooms are never too deep. There is generous open space between and around the buildings, with abundant greenery.

There are, however, some compromises. Unit sizes are 10–30% smaller that the guide recommends. Ceiling heights are 20cm lower than the recommended 2.7m, as was common before the guide came out. Overall sizes of balconies, where provided, are often inadequate.

The three-storey walk-ups have less access to sunshine. Less than half receive the minimum two hours in mid-winter. However, their access to ample outdoor green space may mitigate this problem.

A more significant shortcoming is that none of the four types meet the silver level of the Liveable Housing Design Guidelines – a higher standard of accessibility than the Apartment Design Guide. They fall short on aspects such as being free of steps, door and corridor widths and bathroom configuration. These higher standards are desirable for social housing, as many residents are elderly or have a disability.

Yet renovation could offer remedies. Providing lifts on the courtyard buildings would improve access and reduce the number of units accessed through a single entrance. Small units could be combined into larger living spaces – some units already have been in the 30-storey Matavai and Turanga buildings.

Balconies could also be retrofitted. This, too, has been done already on some of the earliest walk-ups.

Reimagining redevelopment

While the Waterloo buildings have some deficiencies, it’s simply untrue that they are definitively not fit for purpose. Relatively modest renovations or additions could extend the lives of most buildings in a way that supports residents.

There are several examples we can look to for inspiration. Among them are the celebrated work of French architects Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal and the Retain, Repair, Reinvest strategy developed by Melbourne architectural practice OFFICE.

The benefits of redevelopment must be weighed against the impacts of forced relocation on tenants’ health and wellbeing. Older tenants in particular are generally more vulnerable and less likely to benefit.

The decision must also take into account the embodied carbon from the buildings’ construction and the reduction in social housing supply through demolitions – a more significant problem than many realise. If redevelopment is to occur, it must be carefully planned and staged. And it should not preclude upgrades to existing homes in the meantime.

Governments around the country are starting to reinvest in social housing after decades of neglect. It’s more important than ever to recognise the value and potential of what we already have.![]()

Alistair Sisson, Macquarie University Research Fellow, School of Social Sciences, Macquarie University; Cameron Logan, Associate Professor, School of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney; Michael Zanardo, Research Fellow, Department of Architecture, Monash University, and Rebecca McLaughlan, Senior Lecturer in Professional Practice and Architectural Design, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jobs Just For You, The Planning Professional

Our weekly or daily email bulletins are guaranteed to contain only fresh employment opportunities